Q&A: IPCC wraps up its most in-depth assessment of climate change

The final part of the world’s most comprehensive towage of climate transpiration – which details the “unequivocal” role of humans, its impacts on “every region” of the world and what must be washed-up to solve it – has now been published in full by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The synthesis report is the last in the IPCC’s sixth towage cycle, which has involved 700 scientists in 91 countries. Overall, the full trundling of reports has taken eight years to complete.

The report sets out in the clearest and most evidenced detail yet how humans are responsible for the 1.1C of temperature rise seen since the start of the industrial era.

It moreover shows how the impacts of this level of warming are once mortiferous and unduly heaped upon the world’s most vulnerable people.

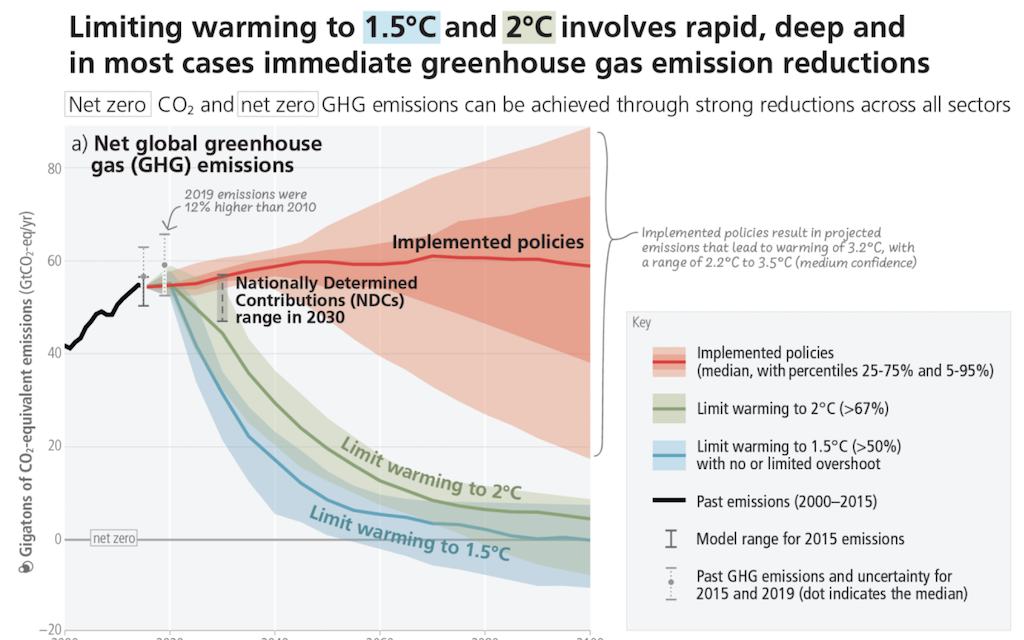

The report notes that policies in place by the end of 2021 – the cut-off stage for vestige cited in the towage – would likely see temperatures exceed 1.5C this century and reach virtually 3.2C by 2100.

In many parts of the world, humans and ecosystems will be unable to transmute to this value of warming, it says. And the losses and damages will “escalate with every increment” of global temperature rise.

But it moreover lays out how governments can still take whoopee to stave the worst of climate change, with the rest of this decade stuff crucial for deciding impacts for the rest of the century. The report says:

“There is a rapidly latter window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all…The choices and deportment implemented in this decade will have impacts now and for thousands of years.”

The report shows that many options for tackling climate transpiration – from wind and solar power to tackling supplies waste and greening cities – are once forfeit effective, enjoy public support and would come with co-benefits for human health and nature.

At a printing briefing, leading climate scientist and IPCC tragedian Prof Friederike Otto said the report highlights “not only the urgency of the problem and the gravity of it, but moreover lots of reasons for hope – considering we still have the time to act and we have everything we need”.

Carbon Brief’s team of journalists has delved through each page of the IPCC’s AR6 full synthesis report to produce a digestible summary of the key findings and graphics.

- 1. What is this report?

- 2. How is the Earth’s climate changing?

- 3. How are human-caused emissions driving global warming?

- 4. How much hotter will the world get this century?

- 5. What are the potential impacts at variegated warming levels?

- 6. How could warming rationalization unreticent and irreversible change?

- 7. What does the report say on loss and damage?

- 8. Why is climate whoopee currently ‘falling short’?

- 9. What is needed to stop climate change?

- 10. How can individual sectors scale up climate action?

- 11. What does the report say well-nigh adaptation?

- 12. What are the benefits of near-term climate action?

- 13. Why is finance an ‘enabler’ and ‘barrier’ for climate action?

- 14. What are the co-benefits for the Sustainable Minutiae Goals?

- 15. What does the report say well-nigh probity and inclusion?

1. What is this report?

The synthesis report is the final part of the IPCC’s sixth towage cycle. It “integrates” the main findings of the three working group reports, which have been published over the last 18 months or so:

- Working Group I (WG1): The physical science basis (August 2021)

- Working Group II (WG2): Impacts, version and vulnerability (February 2022)

- Working Group III (WG3): Mitigation of climate change (April 2022)

The synthesis moreover takes into worth the three shorter “special reports” that the IPCC has published during the sixth towage cycle:

- Global warming of 1.5C (“SR15”) in October 2018

- Climate transpiration and land (“SRCCL”) in August 2019

- The ocean and cryosphere in a waffly climate (“SROCC”) in September 2019

As the “mandate” was to produce a synthesis of existing material, “there is nothing that is in there that is not in the underlying reports”, tragedian Prof Fredi Otto – a senior lecturer at the Grantham Institute for Climate Transpiration and the Environment at Imperial College London – told a printing briefing. This ways that the report does not include any research or emissions pledges issued without the cut-off stage for the WG3 towage – which was 11 October 2021, several weeks surpassing the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow.

The synthesis report is much shorter than the full towage reports. The combined length of the “summary for policymakers” (SPM) – a short, non-technical synopsis – and the underlying report clocks in at 122 pages. This is longer than the 42.5 pages that were planned (pdf), but a fraction of the towage reports that can top 3,000 pages. As with the towage reports, the synthesis report has been through several rounds of review by experts and governments.

The report’s SPM was signed off via a line-by-line clearance session involving authors and government delegates last week in Switzerland.

However, unlike the towage reports, the session also approved the underlying full report “section by section”. It was moreover the IPCC’s first clearance session since the Covid-19 pandemic that was held in person.

The clearance process was scheduled to be completed on Friday 17 March, but overran – despite multiple “night sessions” and “round-the-clock deliberations”. The SPM was finally tried on the morning of Sunday 19 March in a “sparsely attended room”, as many developing country delegates had once left the venue, Third World Network reported. “People who have to contribute have left the meeting,” said India’s representatives in the early hours surpassing the latter plenary.

Once the SPM was approved, there was then a “huge moment of panic” virtually whether “it would at all be possible to do the clearance of the long report”, Otto said:

“We all scrutinizingly died of adrenaline poisoning during [Sunday], but then it was tried quite straightforwardly.”

(The Earth Negotiations Bulletin has published a summary of the discussions during the clearance session. This is referenced commonly in this article.)

The SPM was launched on the afternoon of Monday 20 March with a printing conference. The longer underlying report was then published two days later.

The synthesis report shares the IPCC’s “calibrated language” that the towage reports use to communicate levels of certainty overdue the statements it includes.

The findings are given “as statements of fact or associated with an assessed level of confidence”, based on scientific understanding. The language indicates the “underlying vestige and agreement”, the report explains:

“A level of conviction is expressed using five qualifiers: very low, low, medium, upper and very high, and typeset in italics, for example, medium confidence.

“The pursuit terms have been used to indicate the assessed likelihood of an outcome or result: virtually certain 99-100% probability; very likely 90-100%; likely 66-100%; more likely than not >50-100%; about as likely as not 33-66%; unlikely 0-33%; very unlikely 0—10%; and exceptionally unlikely 0-1%. Spare terms (extremely likely 95-100%; more likely than not >50-100%; and extremely unlikely 0-5%) are moreover used when appropriate.”

The synthesis includes projections based on the latest generation of global climate models, produced as part of the sixth Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) for the AR6 cycle. However, it moreover brings together variegated approaches for how future pathways were considered in the towage reports.

The WG1 report “assessed the climate response to five illustrative scenarios based on Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) that imbricate the range of possible future minutiae of anthropogenic drivers of climate transpiration found in the literature”, the synthesis explains:

“The upper and very upper GHG emissions scenarios (SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5) have CO2 emissions that roughly double from current levels by 2100 and 2050, respectively. The intermediate GHG emissions scenario (SSP2-4.5) has CO2 emissions remaining virtually current levels until the middle of the century. The very low and low GHG emissions scenarios (SSP1-1.9 and SSP1-2.6) have CO2 emissions unthriving to net-zero virtually 2050 and 2070, respectively, followed by varying levels of net-negative CO2 emissions.”

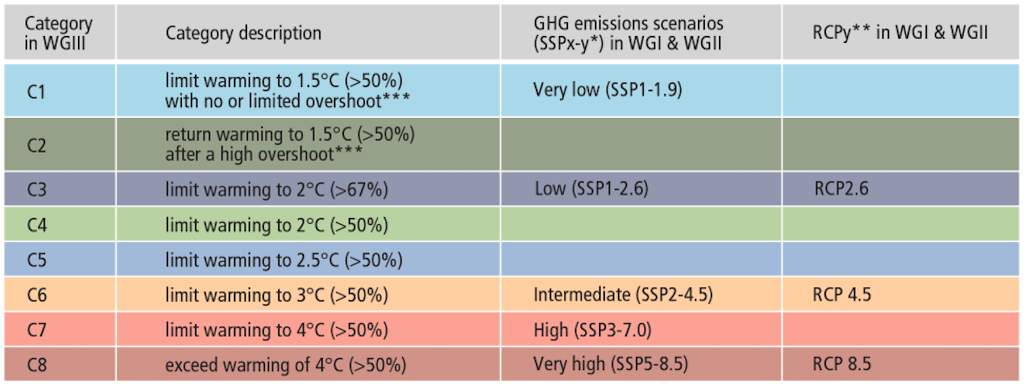

In contrast, the WG3 report assessed “a large number of global modelled emissions pathways…of which 1,202 pathways were categorised based on their projected global warming over the 21st century, with categories ranging from pathways that limit warming to 1.5C with increasingly than 50% likelihood with no or limited overshoot (C1) to pathways that exceed 4C (C8)”.

The table below, taken from the synthesis report, shows how these pathways relate to the SSPs and their predecessors, the Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs).

Description and relationship of scenarios and modelled pathways considered wideness AR6 working group reports. Source: IPCC (2023) Box SPM.1, Table 1

The synthesis report is the final product of the IPCC’s sixth towage cycle. Its delay from the planned publication in September last year for “management reasons” – and the lack of transparency surrounding these issues – resulted in “unusually unmodified statements of discontent from governments” well-nigh the IPCC’s impact and credibility, the Earth Negotiations Bulletin reported at the time.

Nonetheless, governments well-set at a September meeting that the IPCC’s seventh towage trundling (AR7) will uncork in July this year and will have a length of between five and seven years. The end of AR6 and the start of AR7 will see the referendum of a new IPCC leadership team – including chair, vice-chairs and working group co-chairs. The first full towage reports of AR7 would likely not be expected until 2027 or 2028.

2. How is the Earth’s climate changing?

The SPM says with high confidence that human activities have “unequivocally caused global warming”.

This statement – first made in the IPCC’s WG1 report – is the strongest wording to stage well-nigh the role of human activities on observed warming from any IPCC towage cycle.

Overall, the report says that global surface temperature in 2011-20 averaged at 1.09C whilom 1850-1900 levels – with a 1.59C rise seen over land and a 0.88C rise over the ocean. It adds, with high confidence, that “global surface temperature has increased faster since 1970 than in any other 50-year period over at least the last 2000 years”.

According to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin, delegates “disagreed on how much information to include” in the SPM sub-paragraph on global surface temperature increases. The message outlines the lengthy discussion needed to finalise this section of the text – including decisions on whether to use the “more precise” 1.09C or the rounded 1.1C icon and warnings that the wing of uneaten sentences “overloaded the sub-paragraph with numbers and diluted the message”.

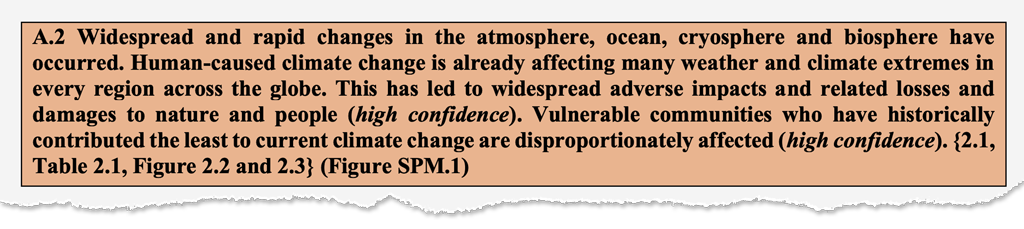

The SPM moreover discusses the observed changes and impacts of climate transpiration to date. It makes the pursuit statement with high confidence:

“Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred. Human-caused climate transpiration is once well-expressed many weather and climate extremes in every region wideness the globe. This has led to widespread wrongheaded impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people.”

It says that global stereotype sea levels increased by 0.2 metres between 1901 and 2018. Sea level rise velocious over this time, from a rate of 1.3mm per year over 1901-71 to 2.7mm per year over 2006-18, it adds.

The SPM for the AR6 synthesis report is longer than its AR5 counterpart (pdf) and contains increasingly numbers in its section on observed changes in the climate system.

For example, the AR5 report does not quantify the rate of velocity of sea level rise, instead saying that “the rate of sea level rise since the mid-19th century has been larger than the midpoint rate during the previous two millennia (high confidence)”.

Meanwhile, the SPM says human influence has likely increased the endangerment of “compound” lattermost events since the 1950s, including increases in the frequency of concurrent heatwaves and droughts.

The SPM has very upper confidence that “increases in lattermost heat events have resulted in human mortality and morbidity” in all regions. It adds that lattermost temperatures moreover rationalization mental health challenges, trauma and the loss of livelihoods and culture. The report moreover has high confidence that climate transpiration is “contributing to humanitarian crises where climate hazards interact with upper vulnerability”.

A man wipes sweat off his brow on a hot day in New Delhi, as South Asia was gripped by a blistering spring heatwave in 2022. Credit: Xinhua / Alamy Stock Photo

Elsewhere, the report has high confidence that unprepossessing and human diseases including zoonoses – infections that pass between animals and people – “are emerging in new areas” and very upper confidence that “the occurrence of climate-related food-borne and water-borne diseases has increased”.

The SPM warns that climate and weather extremes are “increasingly driving ostracism in Africa, Asia, North America (high confidence), and Inside and South America (medium confidence), with small island states in the Caribbean and South Pacific stuff unduly unauthentic relative to their small population size (high confidence)”.

The authors write that hot extremes have intensified in cities and that they have high conviction that the observed wrongheaded impacts are “concentrated amongst economically and socially marginalised urban residents”.

The report elaborates, saying it has high confidence that “urban infrastructure including transportation, water, sanitation and energy systems have been compromised by lattermost and slow-onset events, with resulting economic losses, disruptions of services and impacts to well-being”.

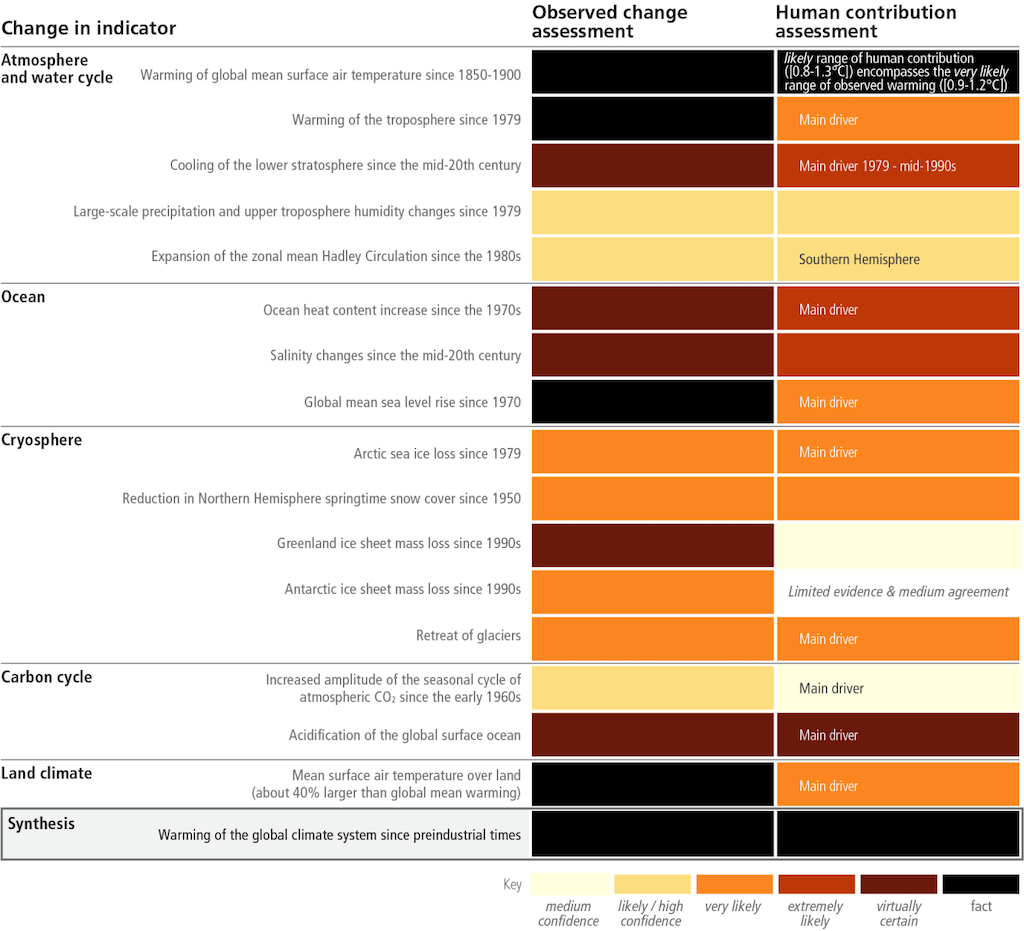

The table unelevated shows observed changes in the climate and their attribution to human influence. Darker colours indicate a higher conviction in the changes and their human influence. Notably, the table lists “warming of the global climate system since pre-industrial times” as a “fact”.

Observed changes in the climate and their attribution to human influence. Darker colours indicate a higher conviction in the findings. Source: IPCC (2023) Table 2.1

The report has high confidence that climate transpiration has hindered efforts to meet the Sustainable Minutiae Goals by reducing supplies security, waffly rainfall patterns, melting persons of ice such as glaciers and driving increasingly intense and frequent lattermost weather events.

For example, the report says that “increasing weather and climate lattermost events have exposed millions of people to vigilant supplies insecurity and reduced water security”. (For increasingly on how climate transpiration is well-expressed lattermost weather, see Carbon Brief’s coverage of the IPCC’s WG1 report.)

The report moreover says that “substantial damages, and increasingly irreversible losses” have once been sustained. For example, it has very upper conviction that approximately half of the species assessed globally have shifted polewards or to higher elevations. It has medium confidence that impacts on some ecosystems are “approaching irreversibility” – for example the impacts of hydrological changes resulting from glacial retreat.

The report moreover has high confidence that “economic impacts owing to climate change are increasingly well-expressed peoples’ livelihoods and are causing economic and societal impacts wideness national boundaries”.

3. How are human-caused emissions driving global warming?

The report states as fact – that is, with no calibrated language – that “human activities, principally through emissions of greenhouse gases, have unequivocally caused global warming”.

In other words, the report states, “human-caused climate transpiration is a magnitude of increasingly than a century of net GHG emissions from energy use, land-use and land use change, lifestyle and patterns of consumption, and production”.

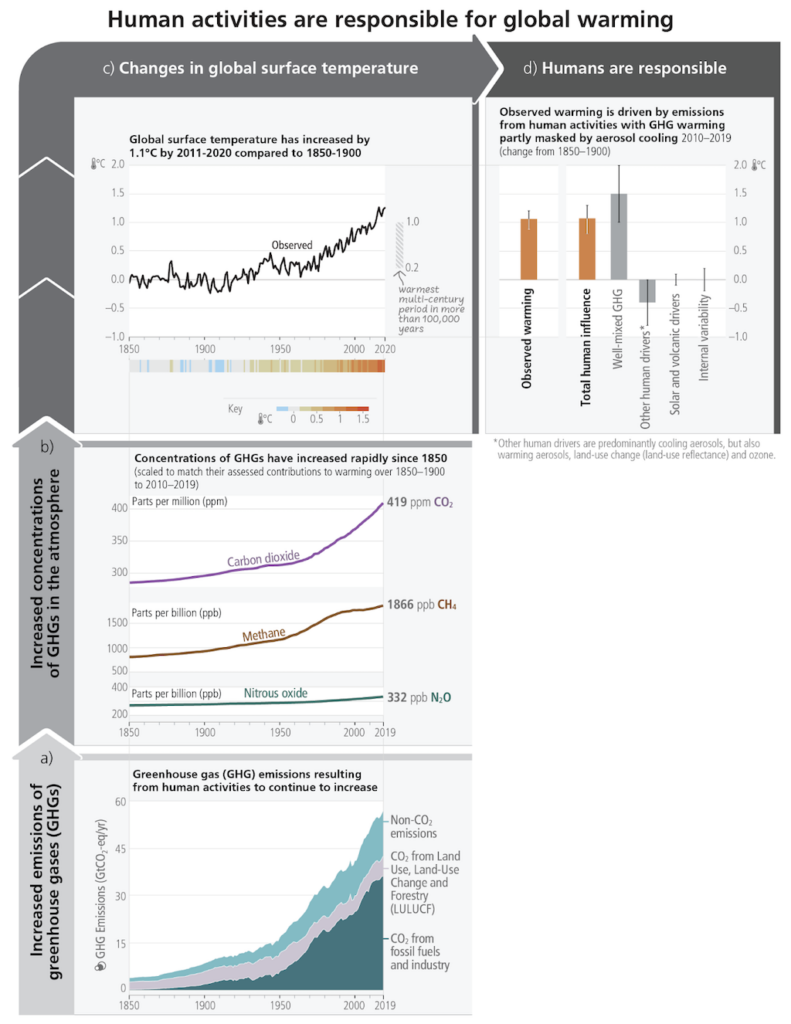

Specifically, the report explains that humans have unsalaried to 1.07C of the observed warming between 1850-1900 and 2010-19, with a likely range of 0.8-1.3C. As the total observed warming over the same period is 1.06C, this ways that humans have caused 100% of the long-term global warming to date.

This conclusion is in line with the synthesis report (pdf) of the IPCC’s fifth towage report (AR5), published in 2014, which said:

“The weightier estimate of the human-induced contribution to warming is similar to the observed warming over [1951-2010].“

That the influence of human worriedness is marginally larger than the observed temperature rise reflects the mix of impacts that an industrialised society is having. The warming impact of the GHGs that human worriedness has produced is likely to be in the range of 1.0-2.0C. But then there is moreover the cooling influence of other “human drivers (principally aerosols)”, the report notes.

Aerosols include tiny particles – such as soot – that are produced from cars, factories and power stations. They tend to have an overall cooling effect on the Earth’s climate by spattering incoming sunlight and stimulating clouds to form. These human drivers could have unsalaried to a cooling of 0.0-0.8C, the IPCC says.

The net cooling effect of human-caused aerosols “peaked in the late 20th century”, the report notes with high confidence.

Natural influences on the climate had only a small influence on the long-term trend in global temperature, the reports says, with fluctuations in the sun and volcanic worriedness causing between -0.1C and 0.1C of temperature transpiration and other natural variability causing between -0.2C and 0.2C.

The increase in concentrations of GHGs in the undercurrent since virtually 1750 “are unequivocally caused by GHG emissions from human activities over this period”, the IPCC says:

“In 2019, atmospheric CO2 concentrations (410 parts per million) were higher than at any time in at least 2m years (high confidence), and concentrations of methane (1866 parts per billion) and nitrous oxide (332 parts per billion) were higher than at any time in at least 800,000 years (very upper confidence).”

The icon unelevated shows “the causal uniting from emissions to resulting warming of the climate system”. The marrow panel shows the increase in GHGs over 1850-2019, the middle panel shows the resulting rise in atmospheric greenhouse gas emissions, the top left panel shows the transpiration in global surface temperature since 1850 and the top right panel separates the warming out into its variegated contributing factors.

The causal uniting from emissions to resulting warming of the climate system. Panel (a) shows the increase in GHGs over 1850-2019. Panel (b) shows the resulting rise in atmospheric greenhouse gas emissions. Panel (c) shows the transpiration in global surface temperature since 1850. Panel (d) separates the warming out into its variegated contributing factors. Source: IPCC (2023) Icon 2.1

The report says with high confidence that “land and ocean sinks have taken up a near-constant proportion (globally well-nigh 56% per year) of CO2 emissions from human activities over the past six decades”. However, looking to the future, it adds:

“In scenarios with increasing CO2 emissions, the land and ocean stat sinks are projected to be less constructive at slowing the unifying of CO2 in the undercurrent (high confidence).

“While natural land and ocean stat sinks are projected to take up, in wool terms, a progressively larger value of CO2 under higher compared to lower CO2 emissions scenarios, they wilt less effective, that is, the proportion of emissions taken up by land and ocean decreases with increasing cumulative net CO2 emissions (high confidence).”

In 2019, global net emissions of GHGs clocked in at 59bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e), the report says. This is 12% higher than in 2010 and 54% higher than in 1990, with “the largest share and growth in gross GHG emissions occurring in CO2 from fossil fuels combustion and industrial processes followed by methane”.

The report says, with high confidence, that GHG emissions since 2010 have increased “across all major sectors”. It continues:

“In 2019, approximately 34% (20GtCO2e) of net global GHG emissions came from the energy sector, 24% (14GtCO2e) from industry, 22% (13GtCO2e) from AFOLU, 15% (8.7GtCO2e) from transport and 6% (3.3GtCO2e) from buildings.”

However, although stereotype yearly GHG emissions between 2010 and 2019 were “higher than in any previous decade”, the rate of growth during this period (1.3% per year) “was lower than that between 2000 and 2009” (2.1% per year), the report notes. This sentence – which moreover featured in the WG3 report – was widow during the clearance session at the request of China, the Earth Negotiations Bulletin reported.

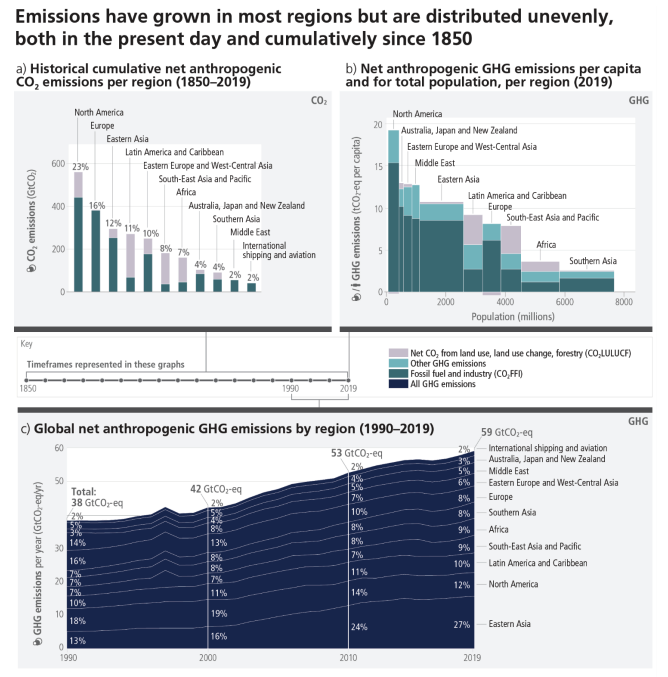

Historical contributions to global GHGs “vary substantially wideness regions” and “continue to differ widely”, the authors note.

In 2019, virtually 35% of the global population were in countries emitting increasingly than nine tonnes of CO2e per capita – excluding CO2 emissions from land use, land-use transpiration and forestry (LULUCF), the report says.

In contrast, 41% were in countries emitting less than three tonnes of CO2e. It adds that least ripened countries (LDCs) and small island developing states (SIDS), in particular, have much lower per-capita emissions (1.7 and 4.6 tonnes of CO2e, respectively) than the global stereotype (6.9 tonnes), excluding CO2 from LULUCF.

Perhaps most starkly, the authors note with high confidence:

“The 10% of households with the highest per-capita emissions contribute 34-45% of global consumption-based household GHG emissions, while the marrow 50% contribute 13-15%.”

The regional variations in emissions are illustrated by the icon below, which shows historical contributions (top-left), per capita emissions in 2019 (top-right) and global emissions since 1990 wrenched lanugo by emissions (bottom). (For increasingly on historical responsibility for emissions, see Carbon Brief’s wringer from 2021.)

During the clearance session, France – supported by virtually 15 other countries, including the US and Canada – requested that this icon was elevated into the SPM “to provide a well-spoken and necessary narrative well-nigh the causes of warming”, the Earth Negotiations Bulletin reported. However, Saudi Arabia, India and China opposed the move and a subsequent huddle was “unable to reach consensus”.

Regional contribution to global GHG emissions. Panel (a) shows the share of historical cumulative net anthropogenic CO2 emissions per region from 1850 to 2019 in GtCO2. Panel (b) shows the distribution of regional per-capita GHG emissions in tonnes CO2e by region in 2019. Both (a) and (b) are separated out by emissions category. Panel (c) shows global net human-caused GHG emissions by region (in GtCO2e per year) for 1990-2019. Percentage values refer to the contribution of each region to total GHG emissions in each respective time period. (The single-year peak of emissions in 1997 was due to a forest and peat fire event in south-east Asia.) Source: IPCC (2023) Icon 2.2

4. How much hotter will the world get this century?

The world will protract to get hotter “in the near term (2021-40)”, the report says, “in nearly all considered scenarios and pathways” for greenhouse gas emissions.

Crucially, however, there is a nomination over how hot it gets by the end of the century. As the synthesis report explains: “Future warming will be driven by future emissions.”

The value of warming this century largely depends on the value of greenhouse gases that humans release into the undercurrent in the future “with cumulative net CO2 dominating”.

In order to stop global warming, the report says, CO2 emissions are, therefore, “require[d]” to reach net-zero. (See: What is needed to stop climate change?)

The report looks at a range of plausible futures, known as the shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs), spanning very low to very upper emissions. (See: What is this report?)

If emissions are very low (SSP1-1.9), then warming is expected to temporarily “overshoot” 1.5C by “no increasingly than 0.1C” surpassing returning to 1.4C in 2100, the report says.

If emissions are very upper (SSP5-8.5), warming could reach 4.4C in 2100. (See unelevated for increasingly on what it would take for the world to follow these variegated emissions pathways.)

Notably, there is less uncertainty in these projections than there was in AR5. This is considering the IPCC has narrowed the range of “climate sensitivity”, using observations of recorded warming to stage and improved understanding of clouds.

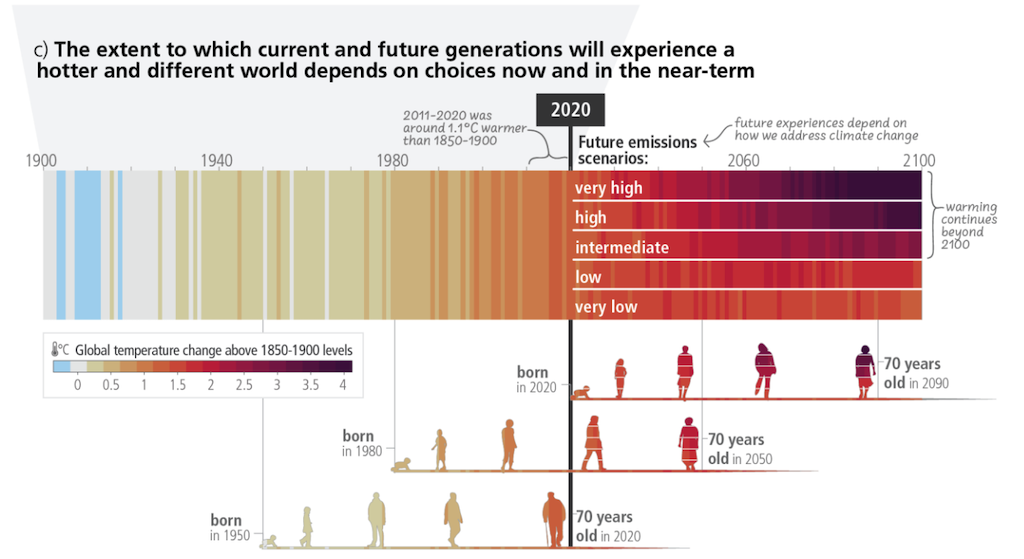

The volitional emissions futures are shown in the icon below, which illustrates the 1.1C of warming to stage and potential increases to 2100 in the style of the famous “climate stripes”.

The icon moreover illustrates the warming that would take place during the lifetimes of three representative generations born in 1950, 1980 and 2020.

Observed (1900-2020) and projected (2021-2100) warming relative to pre-industrial temperatures (1850-1900). Projections relate to very low emissions (SSP1-1.9), low emissions (SSP1-2.6), intermediate emissions (SSP2-4.5), upper emissions (SSP3-7.0) and very upper emissions (SSP5-8.5). Temperatures are colour-coded from the pre-industrial stereotype (blue-grey) through to current warming of 1.1C (orange) and potentially increasingly than 4C by 2100 (purple). Source: IPCC (2023) Icon SPM.1

While limiting warming in line with global targets would require “deep and rapid, and, in most cases, firsthand greenhouse gas emissions reductions in all sectors this decade”, these efforts would not be felt for some time. The SPM explains with high confidence:

“Continued greenhouse gas emissions will lead to increasing warming…Deep, rapid and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions would lead to a discernible slowdown in global warming within virtually two decades.”

This wait ways that global temperatures are more likely than not to reach 1.5C during 2021-40, the report says, plane if emissions are very low.

The report does not requite specific “exceedance” years that violate 1.5C for each emissions pathway. (The 1.5C limit of the Paris Agreement relates to long-term averages, rather than warming in a single year.)

The SPM explains that for very low, low, intermediate and upper emissions, “the midpoint of the first 20-year running stereotype period during which [warming] reaches 1.5C lies in the first half of the 2030s”. If emissions are very high, it would be in “the late 2020s”.

Similarly, the report says warming will exceed 2C this century “unless deep reductions in CO2 and other GHG emissions occur in the coming decades”.

At the other end of the spectrum, it has “become less likely” that the world will match the very upper emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5), where warming exceeds 4C this century.

The report says, with medium confidence, that emissions could only reach such upper levels if there is “a reversal of current technology and/or mitigation policy trends”.

However, it says 4C of warming is possible with lower emissions, if carbon trundling feedbacks or climate sensitivity are larger than thought. It explains in a footnote to the SPM:

“Very upper emissions scenarios have wilt less likely, but cannot be ruled out. Warming levels >4C may result from very upper emissions scenarios, but can moreover occur from lower emission scenarios if climate sensitivity or stat trundling feedbacks are higher than the weightier estimate.”

In wing to the path of greenhouse gas emissions, waffly emissions of “short-lived climate forcers” (SLCFs) can moreover add to near- and long-term warming, the report says with high confidence. SLCFs include methane, aerosols and ozone precursors, it explains.

There have been concerns that efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions could moreover reduce output of cooling aerosols, “unmasking” spare warming. The report plays lanugo this risk:

“Simultaneous stringent climate transpiration mitigation and air pollution tenancy policies limit this spare warming and lead to strong benefits for air quality (high confidence).”

5. What are the potential impacts at variegated warming levels?

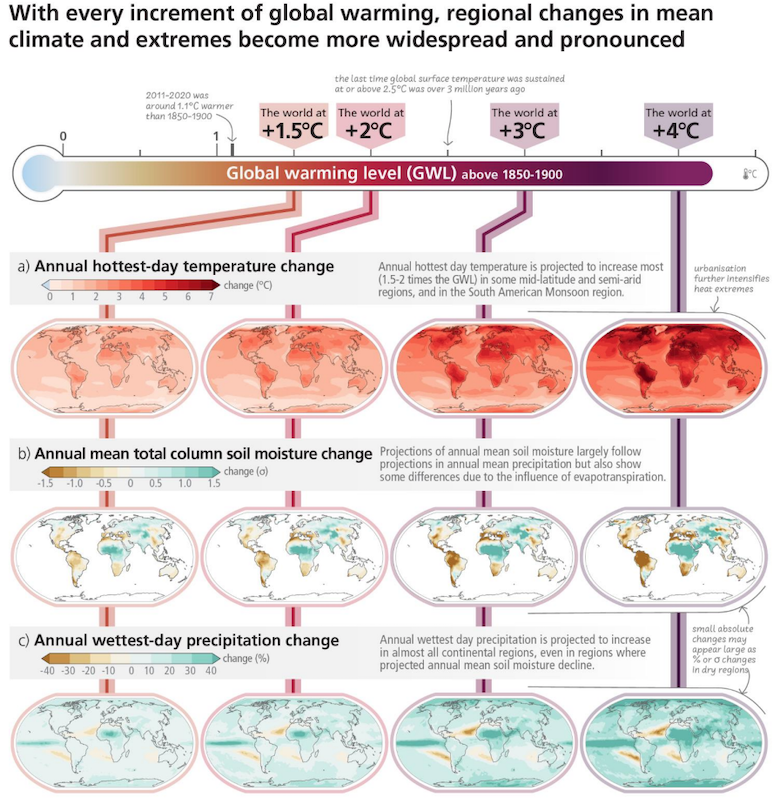

With every uneaten bit of global warming, extremes facing the world will wilt larger, the report says.

For example, it says with high conviction that unfurled climate transpiration will remoter intensify the global water cycle, driving changes to monsoons and to very wet and very dry weather.

As temperatures rise, natural land and ocean stat sinks will be less worldly-wise to swizzle emissions – worsening warming further, the report says with high confidence.

Other changes to expect include remoter reductions in “almost all” the world’s ice systems, from glaciers to sea ice (high confidence), remoter global sea level rise (virtually certain), and increasing venom and decreasing oxygen availability in the oceans (virtually certain).

Every world region will wits increasingly climate impacts with every bit of remoter warming, the report says.

Compound heatwave and drought extremes are expected to wilt increasingly frequent in many regions, the report says with high confidence.

The storm surge from Hurricane Ian sends water through the streets of Naples, Florida in 2022. Credit: Naples Police Department / UPI / Alamy Stock Photo

Extreme sea level events that currently occur once in every 100 years are expected to take place at least annually in increasingly than half all measurable locations by 2100, under any future emissions scenario, it says with high confidence. (Extreme sea level events include storm surges and flooding.)

Other projected changes include the intensification of tropical storms (medium confidence) and increases in fire weather (high confidence), equal to the report.

It says that the natural variability of the Earth’s climate will protract to act slantingly climate change, sometimes worsening and sometimes masking its effects.

The graphic below, from the report’s SPM, illustrates some of the regional impacts of climate transpiration at 1.5C, 2C, 3C and 4C of global warming. (Current policies from governments have the world on track for virtually 2.7C of warming.)

A selection of regional climate impacts at 1.5C, 2C, 3C and 4C of global warming. [The world is currently on track for 2.7C]. Source: IPCC (2023) Icon SPM.2

In the near term, every world region is expected to squatter remoter increases in climate hazards – with rising risk for humans and ecosystems (very upper confidence), the report says.

Risks expected to increase in the near-term include heat-related deaths (high confidence), food-, water- and vector-borne diseases (high confidence), poor mental health (very upper confidence), flooding in coastal and low-lying cities (high confidence) and a subtract in supplies production in some regions (high confidence).

At 1.5C, risks will increase for “health, livelihoods, supplies security, water supply, human security and economic growth”, the report says. At this level of global warming, many low-elevation and small glaciers virtually the world would lose most of their mass or disappear, the report says with high confidence. Coral reefs are expected to ripen by a remoter 70–90%, it adds with high confidence.

At 2C, risks associated with lattermost weather events will transition to “very high”, the report says with medium confidence. At this level of warming, changes in supplies availability and nutrition quality could increase nutrition-related diseases and undernourishment for up to “hundreds of millions of people”, particularly among low-income households in sub-Saharan Africa, south Asia and inside America, the report says with high confidence.

At 3C, “risks in many sectors and regions reach upper or very upper levels, implying widespread systemic impacts”, the report says. The number of theirs species in biodiversity hotspots at a very upper risk of extinction is expected to be 10 times higher than at 1.5C, it says with medium confidence.

At 4C and above, virtually half of tropical marine species could squatter local extinction, the report says with medium confidence. Virtually four billion people could squatter water scarcity, it says with medium confidence. It adds that the global zone burned by wildfires could increase by 50-70% (medium confidence).

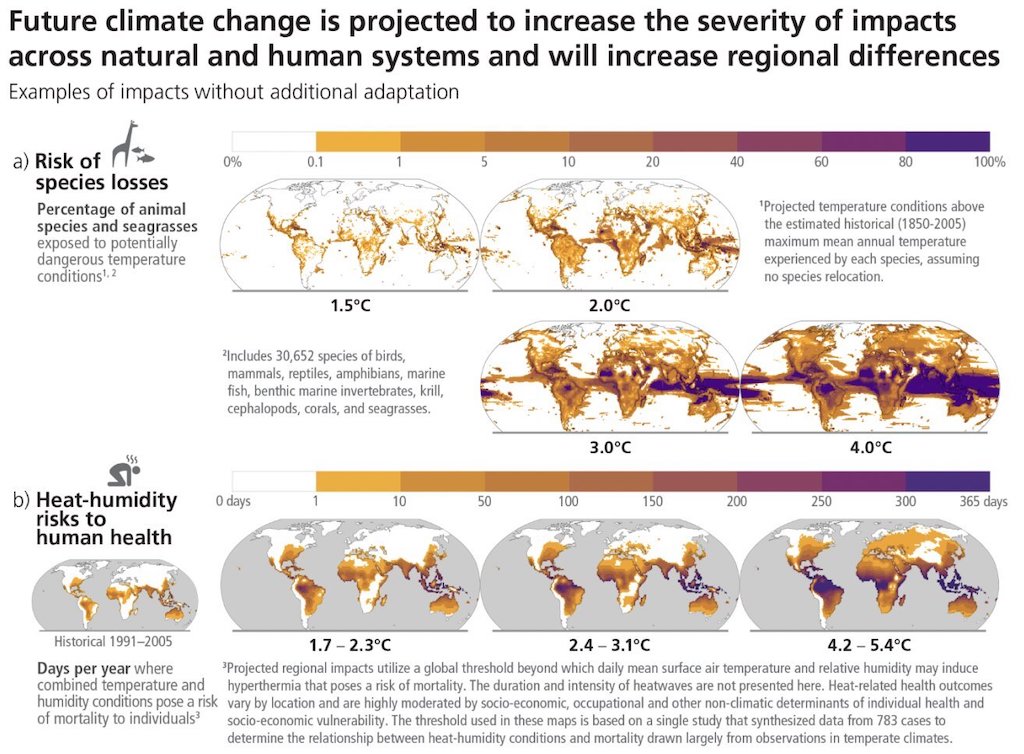

The graphic below, from the report’s SPM, illustrates the risks facing Earth’s species (a) and human health risk from lattermost heat-humidity (b) under variegated levels of global warming.

It shows that, at temperatures whilom 2C, some regions will see all of their wildlife exposed to dangerous temperatures, thesping the species do not relocate to somewhere else.

It moreover shows that, whilom 2C, some people will live in regions where temperature and humidity conditions are mortiferous every day of the year.

Risks to species and humans at various levels of global warming. Source: IPCC (2023) SPM.3a and b

The risks identified in this report are larger at lower levels at warming, when compared to the IPCC’s last assessment in 2014.

This is considering of new vestige from climate extremes once recorded, improved scientific understanding, new knowledge on how some humans and species are increasingly vulnerable than others and a largest grasp of the limits to adaptation, the report says with high confidence.

Because of “unavoidable” sea level rise, risks for coastal ecosystems, people and infrastructure will protract to increase vastitude 2100, it adds with high confidence.

As climate transpiration worsens, risks “will wilt increasingly ramified and increasingly difficult to manage”, the report says.

Climate transpiration is likely to recipe other societal issues, it says. For example, supplies shortages driven by warming are projected to interact with other factors, such as conflicts, pandemics and competition over land, the report says with high confidence.

Most pathways for how the world can meet its would-be 1.5C temperature involve a period of “overshoot” where temperatures exceed this level of warming temporarily surpassing dropping when down.

During this period of overshoot, the world would see “adverse impacts” that may worsen climate change, such as increased wildfires, mass mortality of ecosystems and permafrost thawing, the report says with medium confidence.

The report adds that solar geoengineering – methods for reflecting yonder sunlight to reduce temperature rise – has the “potential to offset warming within one or two decades and untie some climate hazards”, but could moreover “introduce a widespread range of new risks to people and ecosystems” and “would not restore climate to a previous state”.

6. What are the risks of unreticent and irreversible change?

The report warns that unfurled emissions of GHGs will “further stupefy all major climate system components and many changes will be irreversible on centennial to millennial timescales”.

While “many changes in the climate system” will wilt larger “in uncontrived relation to increasing global warming”, the likelihood of “abrupt and/or irreversible outcomes increases with higher global warming levels”, the report says with high confidence. For example, it says:

“As warming levels increase, so do the risks of species extinction or irreversible loss of biodiversity in ecosystems such as forests (medium confidence), coral reefs (very upper confidence) and in Arctic regions (high confidence).”

The impacts of warming on some ecosystems are once “approaching irreversibility”, the report says, “such as the impacts of hydrological changes resulting from the retreat of glaciers, or the changes in some mountain (medium confidence) and Arctic ecosystems driven by permafrost thaw (high confidence)”.

Abrupt and irreversible changes can include those “triggered when tipping points are reached”, the report says:

“Risks associated with large-scale singular events or tipping points, such as ice sheet instability or ecosystem loss from tropical forests, transition to upper risk between 1.5C-2.5C (medium confidence) and to very upper risk between 2.5C-4C (low confidence).”

(See Carbon Brief’s explainer for increasingly on tipping points.)

The report has upper conviction that “the probability of low-likelihood outcomes associated with potentially very large impacts increases with higher global warming levels”. The impact of these unreticent changes would be dramatic.

Citing an example of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a major system of currents in the Atlantic Ocean that brings warm water up to Europe from the tropics and beyond, the report says:

“[AMOC] is very likely to weaken over the 21st century for all considered scenarios (high confidence), however an unreticent swoon is not expected surpassing 2100 (medium confidence). If such a low probability event were to occur, it would very likely rationalization unreticent shifts in regional weather patterns and water cycle, such as a southward shift in the tropical rain belt, and large impacts on ecosystems and human activities.”

For comparison, the AR5 synthesis report moreover terminated that a weakening of AMOC was very likely, but said that an unreticent transition or swoon in the 21st century was very unlikely.

The report notes that “low-likelihood, high-impact outcomes could occur at regional scales plane for global warming within the very likely assessed range for a given GHG emissions scenario”.

The report has a particularly stark towage on the projected impacts of global warming on the ocean. The authors warn, with high confidence, that sea level rise is “unavoidable for centuries to millennia due to standing deep ocean warming and ice sheet melt”. And levels will “remain elevated for thousands of years”.

While the authors are virtually certain that sea level rise will protract through this century, “the magnitude, the rate, the timing of threshold exceedances, and the long-term transferral of sea level rise depend on emissions, with higher emissions leading to greater and faster rates of sea level rise”.

Over the next 2,000 years, global stereotype sea level “will rise by well-nigh 2-3 metres if warming is limited to 1.5C and 2-6 m if limited to 2C”, the report says, with low confidence.

Warming vastitude 2C could put the Earth’s massive ice sheets at risk, the report says:

“At sustained warming levels between 2C and 3C, the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets will be lost scrutinizingly completely and irreversibly over multiple millennia (limited evidence).”

These projections of sea level rise wideness thousands of years are “consistent with reconstructed levels during past warm climate periods”, the report notes.

For example, it says with medium confidence, “global midpoint sea level was very likely 5-25 metres higher than today roughly 3m years ago, when global temperatures were 2.5-4C higher than 1850-1900”.

In wing to rising sea levels, the authors say it is virtually certain that ocean acidification – where seawater becomes less alkaline – will protract throughout this century. And they have high confidence that deoxygenation – the ripen in oxygen levels in the ocean – will too.

The report moreover cautions that the value of warming – and the impact it would have – could be increasingly severe than projected.

For example, it says, “warming substantially whilom the assessed very likely range for a given scenario cannot be ruled out, and there is high confidence this would lead to regional changes greater than assessed in many aspects of the climate system”.

On sea levels, the authors add:

“Global midpoint sea level rise whilom the likely range – unescapable two metres by 2100 and in glut of 15 metres by 2300 under a very upper GHG emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5) (low confidence) – cannot be ruled out due to deep uncertainty in ice-sheet processes and would have severe impacts on populations in low elevation coastal zones.”

7. What does the report say on loss and damage?

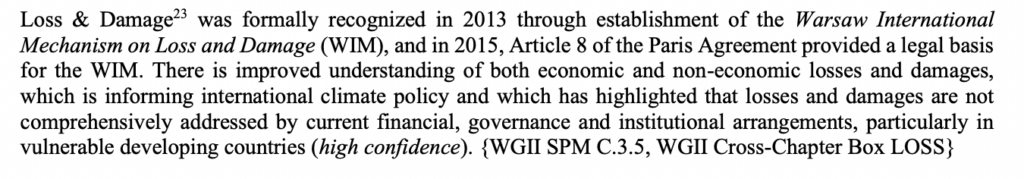

For the first time ever, the term “loss and damage” is mentioned in an IPCC synthesis report. This reflects its prominence in the 1.5C special report and WG2 report during the sixth towage cycle.

The report explains the formal recognition of loss and forfeiture via the Warsaw Mechanism on Loss and Damage and the Paris Agreement.

It acknowledges that there has been an “improved understanding” of what constitutes economic and non-economic losses and damages. In turn, this has served to inform climate policy as well as highlight governance, financial and institutional gaps in how it is stuff addressed.

The AR6 synthesis report mentions the formal recognition of “loss and damage”. Source: IPCC (2023) Full report p18

After this single mention, the report discusses “losses and damages” increasingly broadly. These, it defines in a footnote in the SPM, are the “adverse observed impacts and/or projected risks and can be economic and/or non-economic”.

Including loss and forfeiture in the IPCC’s assessments has been a fraught process. The use of two separate terms separates the scientific “losses and damages” from the political debate of “loss and damage” under the UNFCCC, plane as impacted countries hope to connect the two.

In the plenary discussions, Grenada – supported by Senegal, Antigua and Barbuda, Timor Leste, Kenya and Tanzania – wanted vulnerable countries to be referenced and the differences between the two terms explicitly clarified, given that “the stardom is often troublemaking to people outside of the IPCC”. The US, meanwhile, supported putting a definition in the footnote.

On the impacts of climate change, the report recognises and reviews “strengthened” vestige of heatwaves, lattermost rainfall, droughts and tropical cyclones, plus their attribution to human influence, since the last synthesis report.

In all regions, lattermost heat events have resulted in human mortality and morbidity, it says with very upper confidence, while climate-related food-borne and water-borne diseases have increased. Climate transpiration is moreover contributing to humanitarian crises “where climate hazards interact with upper vulnerability”, the report states with high confidence.

Climate transpiration has caused “substantial damages, and increasingly irreversible losses” in land-based, freshwater, coastal, ocean and unshut ecosystems, as well as in glaciers and continental ice sheets, the report’s summary says with high confidence.

The A2 headline statement from the SPM that authors “spent hours crafting” to reflect vulnerability and impacts on human and natural systems. IPCC (2023) SPM p5

The widespread “losses and damages to nature and people” are unequally distributed wideness systems, regions and sectors”, says the report’s summary, pointing to both economic and non-economic losses.

Sectors such as agriculture, forestry, fishery, energy, and tourism that are “climate exposed” have experienced economic damages from climate change, the report states with high confidence.

Across the world, non-economic loss and forfeiture impacts, such as mental health challenges, were associated with trauma from lattermost weather events and loss of livelihoods and culture. (According to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin, India requested that mental health not be included in these impacts, which Finland opposed.)

The report says with high conviction that “vulnerable communities who have historically unsalaried the least to current climate transpiration are disproportionately affected”.

For example, fatalities from floods, droughts and storms were 15 times higher in highly vulnerable regions between 2010 to 2020, compared to regions with very low vulnerability, it states with upper confidence.

In urban areas, losses and damages are “concentrated” in communities of economically and socially marginalised residents, the report notes.

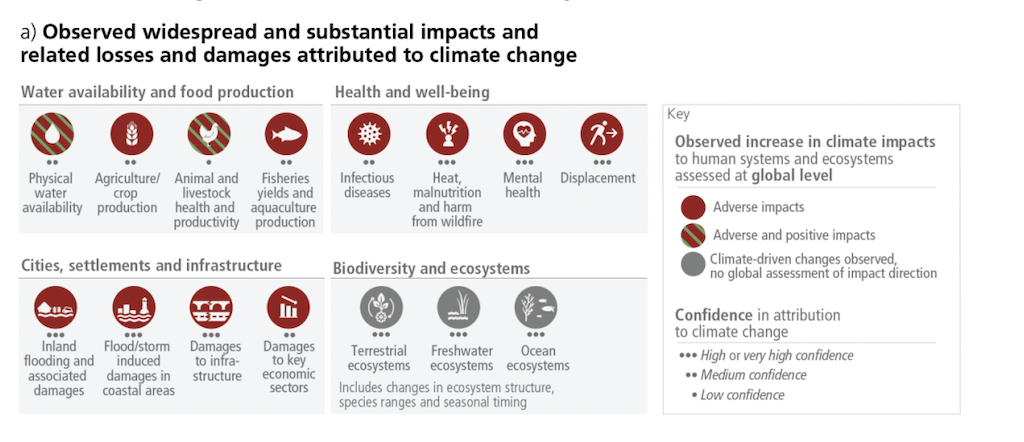

The icon unelevated shows observed impacts on human systems and ecosystems attributed to climate transpiration at global and regional levels, withal with conviction in their attribution to climate change.

Observed and widespread impacts and related losses and damages attributed to climate change. Mental health and ostracism impacts are limited to only regions assessed. Conviction levels reflect attribution studies so far. Source: IPCC (2023), Icon SPM1a

The report states with very upper conviction that “losses and damages escalate with every increment of global warming”.

These will be higher at 1.5C and plane higher at 2C, the report’s summary states. Compared to AR5, “global aggregated risk levels” will be upper to very upper plane at lower warming levels, owing to an improved understanding of exposure, vulnerability and recent evidence, including “limits to adaptation”. Climatic and non-climatic risks will increasingly interact, leading to “compound and cascading risks” that are difficult to manage.

However, near-term climate deportment that rein in global warming to “close to 1.5C” could “substantially reduce” losses and damages to humans and ecosystems. Still, plane these deportment “cannot eliminate them all”, the report notes.

Overall, the magnitude and rate of future losses and damages “depend strongly” on near-term mitigation and version actions, the report says with very upper confidence.

Without both, “losses and damages will protract to unduly stupefy the poorest and most vulnerable”, the report says, subtracting that “accelerated financial support for developing countries from ripened countries and other sources is a hair-trigger enabler for mitigation action”. (See: Why is finance an ‘enabler’ and ‘barrier’ for climate action?)

Delaying mitigation will only increase warming, which could derail the effectiveness of version options, it says with high confidence, leading to increasingly climate risks and related losses and damages.

However, the report and its summary warn with high conviction that “adaptation does not prevent all losses and damages”. The authors point out with high confidence that some ecosystems, sectors and regions have once hit limits to how much they can transmute to climate impacts. In some cases, adaptive deportment are unfeasible – that is, they have “hard limits” – for unrepealable natural systems or are simply not an option considering of socioeconomic or technological barriers – known as “soft limits” – leading to unavoidable loss and forfeiture impacts.

“One of the new messages in this report is that it powerfully busts the myth of uncounted adaptation,” said report tragedian Dr Aditi Mukherji, director at the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), speaking at a printing conference.

8. Why is climate whoopee currently ‘falling short’?

Current pledges for how countries will cut emissions by 2030 make it likely that global warming will exceed 1.5C this century and will make it harder to limit temperatures to 2C, equal to one of the headline findings of the report.

The establishment of the Paris Agreement – the landmark climate deal reached in 2015 – has led to increasingly target-setting and “enhanced transparency” for climate action, the report says with medium confidence.

At the same time, there has been “rising public awareness” well-nigh climate transpiration and an “increasing diversity” of people taking action. These efforts “have overall helped slide political transferral and global efforts to write climate change”, the report says, adding:

“In some instances, public discourses of media and organised counter movements have impeded climate action, exacerbating helplessness and disinformation and fuelling polarisation, with negative implications for climate whoopee (medium confidence).”

It says with high conviction that many rules and economic tools for tackling emissions have been “deployed successfully” – leading to enhanced energy efficiency, less deforestation and increasingly low-carbon technologies in many countries. This has in some cases lowered emissions.

By 2020, laws for reducing emissions were in place in 56 countries – tent 53% of global emissions, the report says.

At least 18 countries have seen their production and consumption emissions fall for at least 10 years, it adds. But these reductions have “only partly offset” global emissions increases.

The report adds that there are several options for tackling climate transpiration that are “technically viable”, “increasingly forfeit effective” and are “generally supported by the public”.

This includes solar and wind power, the greening of cities, boosting energy efficiency, protecting forests and grasslands, reducing food waste and increasing the electrification of urban systems.

It adds that, over 2010-19, there have been large decreases in the unit financing of solar power (85%), wind (55%) and lithium ion batteries (85%). In many regions, electricity from solar and wind is now cheaper than that derived from fossil fuels, the report says.

A crane is used to hoke an agricultural photovoltaic system in Lüchow, Germany on November 3, 2021. Credit: Philipp Schulze / dpa / Alamy Stock Photo

(According to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin, a group of countries including Germany, Denmark and Norway strongly argued for the report to highlight that renewables are now cheaper than fossil fuels in many regions. Finland suggested subtracting that fossil fuels are the “root cause” of climate change, but this was strongly opposed by Saudi Arabia.)

At the same time, there have been “large increases in their deployment”, including a global stereotype of 10 times for solar and 100 times for electric cars, the report says.

Falling financing and increased deployment have been boosted by public research and funding and demand-side policies such as subsidies, it says, adding:

“Maintaining emission-intensive systems may, in some regions and sectors, be increasingly expensive than transitioning to low-emission systems (high confidence).”

(According to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin, India, supported by Brazil, said the sentence “favoured ripened countries as it did not reference feasibility and challenges”.)

Despite this, a “substantial emissions gap” remains between what global GHG emissions are projected to be in 2030 and what they must be if the world is to limit global warming to 1.5C or 2C, the report says with high confidence. (The 2030 projections are derived from country climate pledges made prior to COP26 in 2021.)

This gap would “make it likely that warming will exceed 1.5C during the 21st century”, the report says with high confidence.

Pathways for how the world can limit global warming to 1.5C or 2C depend on deep global emissions cuts this decade, it adds with high confidence.

The report says with medium confidence that country climate plans superiority of COP26 would lead to virtually 2.8C of warming (range from 2.1-3.4C) by 2100.

However, it adds with high confidence that policies put in place by countries by the end of 2020 would not be sufficient to unzip these climate plans. This represents an “implementation gap”.

When just policies put in place by the end of 2020 are considered, virtually 3.2C of warming (range 2.2-3.5C) is projected by 2100, the report says with medium confidence.

The orchestration below, from the SPM, illustrates the warming expected in 2100 from policies implemented by 2020 (red), as well as what emissions cuts would need to squint like to reach 1.5C (blue) or 2C (green).

Expected warming in 2100 from policies implemented by the end of 2020 (red), compared with emissions cuts needed to limit warming to 1.5C (blue) or 2C (green). Source: IPCC (2023) SPM.5

Speaking during a printing briefing, Prof Peter Thorne, director of the ICARUS Climate Research Centre at Maynooth University in Ireland and synthesis report author, noted that the IPCC’s towage had a cut-off stage of surpassing COP26 in 2021. He explained:

“Additional implemented policies since the cut-off stage would lead to those curves drawing lanugo a little bit, compared to where they are. But everything that has happened since the IPCC cut-off – which is outside the telescopic of this synthesis report – would suggest that we’re still some way off.”

(A November 2022 assessment from the self-sustaining research group Climate Whoopee Tracker found that country climate plans for 2030 in place by that time would rationalization 2.4C (range 1.9-2.9C) of warming. Policies in place by that time would rationalization 2.7C (range 2.2-3.4C), it added.)

The report moreover notes that many countries have signalled intentions to unzip net-zero greenhouse gas or CO2 emissions by 2050. However, it says such pledges differ “in terms of telescopic and specificity, and limited policies are to stage in place to unhook on them”.

In most developing countries, the rollout of low-carbon technologies is lagging behind, the report adds. This is due in part to a lack of finance and technology transfer from ripened countries, it says with medium confidence.

The leveraging of climate finance for developing countries has slowed since 2018, the report says with high confidence. It adds:

“Public and private finance flows for fossil fuels are still greater than those for climate version and mitigation (high confidence).”

9. What is needed to stop climate change?

“There is a unenduring and rapidly latter window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all,” the report says with high confidence.

The synthesis delivers a unmodified message on what will be needed to stop climate change, saying “limiting human-caused warming requires net-zero CO2 emissions”.

(The Earth Negotiations Bulletin says there was debate over this opening sentence in section B5 of the SPM. It reports: “The authors said that a fundamental insight of AR6 is that, to hold warming at any level, net-zero [CO2] emissions are required at some point.)

The report goes on to say, with high confidence, that reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions would imply net-negative CO2 – and would “result in a gradual decline in surface temperatures”.

Reaching net-zero emissions requires “rapid and deep and, in most cases, immediate

greenhouse gas emissions reductions in all sectors this decade”, equal to the report.

Repeating language from the underlying WG3 report, it adds that global GHG emissions must peak “between 2020 and at the latest surpassing 2025” to alimony warming unelevated 1.5C or 2C.

In unrelatedness with the uncontrived wording on net-zero, the report barely mentions coal, oil and gas.

A lignite excavator operates in the Garzweiler II opencast lignite mine near the village Luetzerath, in Jackerath, Germany, on January 5, 2023. Credit: Rolf Vennenbernd/dpa via AP / Alamy Stock Photo

However, it does say net-zero would midpoint a “substantial reduction in overall fossil fuel use”.

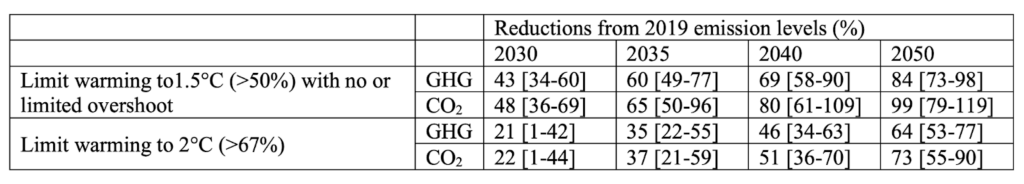

Staying unelevated 1.5C or 2C depends on cumulative stat emissions at the time of reaching net-zero CO2 and the level of greenhouse gas emissions cuts this decade, the report says.

Specifically, net-zero CO2 needs to be reached “in the early 2050s” to stay unelevated 1.5C:

“Pathways that limit warming to 1.5C (>50%) with no or limited overshoot reach net-zero CO2 in the early 2050s, followed by net-negative CO2 emissions. Those pathways that reach net-zero GHG emissions do so virtually the 2070s. Pathways that limit warming to 2C (>67%) reach net-zero CO2 emissions in the early 2070s.”

(There was some ravages on this point without a speech by UN secretary-general António Guterres launching the IPCC report. Guterres tabbed for global net-zero emissions by 2050, with ripened countries going faster, but did not say if he was referring to CO2 or GHGs.)

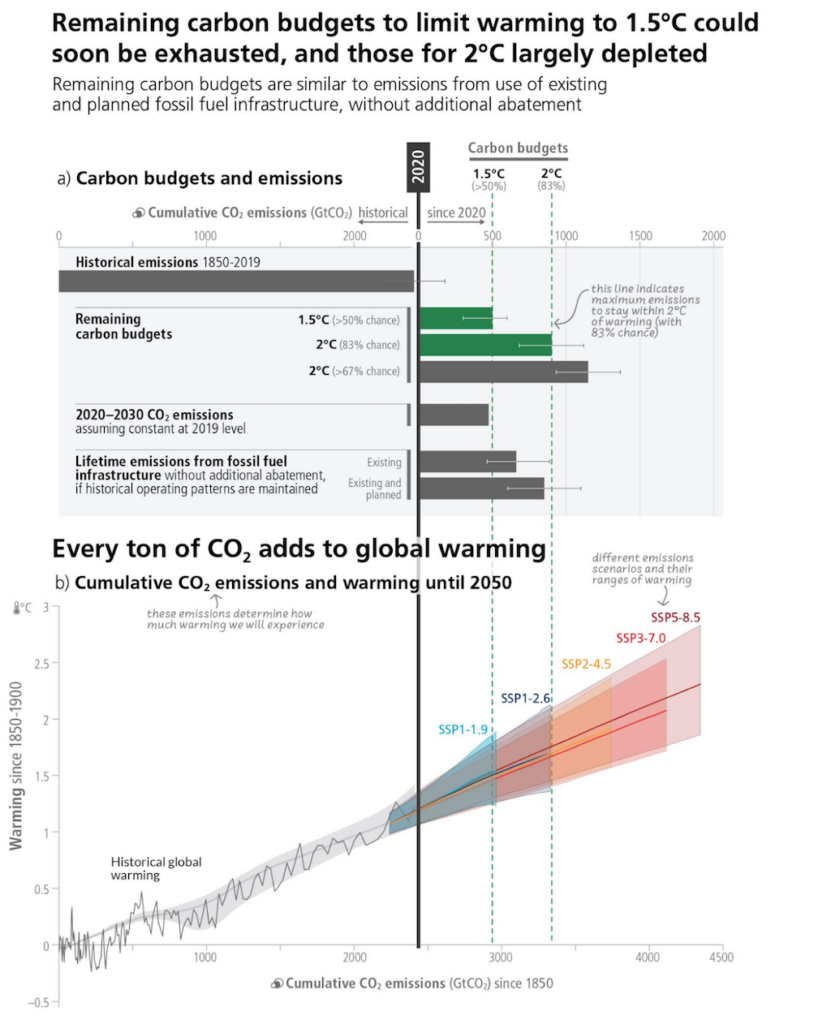

There is a uncontrived link between cumulative stat emissions and warming, with the report saying that every 1,000GtCO2 raises temperatures by 0.45C. The report says with high confidence:

“From a physical science perspective, limiting human-caused global warming to a specific level requires limiting cumulative CO2 emissions, reaching at least net-zero CO2 emissions, withal with strong reductions in other greenhouse gas emissions.”

This results in “carbon budgets” that must not be exceeded if the world is to limit warming to a given level. As of the start of 2020, the remaining upkeep to requite a 50% endangerment of staying unelevated 1.5C is 500GtCO2, rising to 1,150GtCO2 for a 67% endangerment of staying unelevated 2C.

(Stronger reductions of non-CO2 emissions would midpoint a larger stat upkeep for a given temperature limit, the report notes, and vice versa.)

Some four-fifths of the total upkeep for 1.5C has once been used up during 1850-2019 and the last fifth would be “almost exhaust[ed]” by 2030, if emissions remained at 2019 levels.

In order to stay within the upkeep for 1.5C, global greenhouse gas emissions would need to fall to 43% unelevated 2019 levels by 2030 and to 60% unelevated by 2035, falling 84% by 2050.

Even faster reductions are required for CO2 emissions, which would fall to 48% unelevated 2019 levels by 2030, 65% by 2035 and 99% by 2050, when they would powerfully hit net-zero.

The synthesis report lists these numbers in a new table, below. While the information is not new, it had not previously been presented in an wieldy format. It was widow during the week-long clearance process and is labelled “Table XX”.

Central (median) CO2 and GHG reductions in 2030, 2035, 2040 and 2050, relative to 2019 levels, in 97 “C1” scenarios that have a greater than 50% endangerment of limiting warming to 1.5C with no or limited overshoot, and in 311 “C3” scenarios that have a 67% endangerment of limiting warming to 2C. Numbers in square brackets indicate 5th to 95th percentile ranges wideness the scenarios. Note that most of these scenarios are designed to cut emissions globally at “least-cost”, meaning they “do not make explicit assumptions well-nigh global equity, environmental justice or intraregional income distribution”. Source: IPCC (2023) Table XX.

At a rundown for journalists held by the UK Science Media Centre, Dr Chris Jones, synthesis report tragedian and research fellow at the UK’s Met Office, said: “We hope, obviously, this information is useful for the stocktake process.”

(This refers to the “global stocktake” of progress to stage and the efforts needed to meet international climate goals, which is taking place this year as part of the UN climate process.)

The report outlines how the world could reach net-zero CO2 emissions via a “substantial reduction in overall fossil fuel use, minimal use of unabated fossil fuels, and use of stat capture and storage (CCS) in the remaining fossil fuel systems”.

(The phrase “unabated fossil fuels” is specified in a footnote to the report, by comparison with “abatement”, which it says would midpoint “capturing 90% or increasingly CO2 from power plants, or 50–80% of fugitive methane emissions from energy supply”.)

While the world needs to make “deep and rapid” cuts in gross emissions, the use of CO2 removal (CDR) is moreover “unavoidable” to reach net-zero, the report says with high confidence.

The report explains:

“[P]athways reaching net-zero CO2 and GHG emissions include transitioning from fossil fuels without stat capture and storage (CCS) to very low- or zero-carbon energy sources, such as renewables or fossil fuels with CCS, demand-side measures and improving efficiency, reducing non-CO2 GHG emissions, and CDR.”

CDR will be needed to “counterbalance” hard-to-abate residual emissions in some sectors, for example “some emissions from agriculture, aviation, shipping and industrial processes”.

(For increasingly detail on sectoral transitions needed to reach net-zero, see: How can individual sectors scale up climate action?)

Emphasising the rencontre of limiting warming, the report says the fossil fuel infrastructure that has once been built would be unbearable to violate the 1.5C stat budget, if operated in line with historical patterns and in the sparsity of uneaten abatement.

This is shown in the icon below. The top panel shows historical emissions and the remaining budgets for 1.5C or 2C, as well as emissions this decade if they remain at 2019 levels and the emissions of existing and planned fossil fuel infrastructure.

The lower panel shows historical warming and potential increases by 2050, in relation to the stat budgets and the range of possible emissions over the same period.

Cumulative past, projected and “committed” CO2 emissions from existing and planned fossil fuel infrastructure, GtCO2, and associated global warming. Source: IPCC (2023) Icon 3.5.

Delaying emissions cuts risks “lock-in [of] high-emissions infrastructure”, the report states, subtracting with high confidence that this would “raise risks of stranded resources and cost-escalation, reduce feasibility, and increase losses and damages”.

The report notes that only “a small number of the most would-be global modelled pathways” stave temporary overshoot of the 1.5C target. However, warming “could gradually be reduced then by achieving and sustaining net-negative global CO2 emissions”.

On the other hand, the IPCC warns of “additional risks” as a result of overshoot, specified as exceeding a warming level and returning unelevated it later. It states with high confidence:

“Overshoot entails wrongheaded impacts, some irreversible, and spare risks for human and natural systems, all growing with the magnitude and elapsing of overshoot.”

The report adds that some of these impacts could make it harder to return warming to lower levels, stating with medium confidence:

“Adverse impacts that occur during this period of overshoot and rationalization spare warming via feedback mechanisms, such as increased wildfires, mass mortality of trees, drying of peatlands, and permafrost thawing, weakening natural land stat sinks and increasing releases of GHGs would make the return increasingly challenging.”

It says the risks virtually overshoot, as well as the “feasibility and sustainability concerns” for CDR, can be minimised by faster whoopee to cut emissions. Similarly, minutiae pathways that use resources increasingly efficiently moreover minimise dependence on CDR.

10. How can individual sectors scale up climate action?

In order to limit warming to 2C or unelevated by the end of the century, all sectors must undergo “rapid and deep, and in most cases, firsthand greenhouse gas emissions reductions”, the report says.

Limiting warming to 1.5C with “no or limited overshoot” requires achieving net-zero CO2 emissions in the early 2050s. To alimony warming to 2C, net-zero CO2 must be achieved “around the early 2070s”.

It continues, with medium confidence:

Source: IPCC (2023) Full report, p68

Reducing emissions from the energy sector requires a combination of actions, the report says: a “substantial reduction” in the use of fossil fuels; increased deployment of energy sources with zero or low emissions, “such as renewables or fossil fuels with CO2 capture and storage” (CCS); improving energy efficiency and conservation; and “switching to volitional energy carriers”.

For sectors that are harder to decarbonise, such as shipping, aviation, industrial processes and some agriculture-related emissions, the report notes that using stat dioxide removal (CDR) technologies to weigh these residual emissions “is unavoidable”.

Direct Air Capture fans on the roof of a garbage incinerator in Hinwil outside Zurich. Orjan Ellingvag / Alamy Stock Photo

The language virtually CCS and CDR was some of the most contentious during the clearance session. Equal to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin, Germany “suggested including a unenduring overview of the feasibility and current deployment of variegated CDR methods”, with France subtracting that policymakers must be made enlightened of the associated challenges.

But Saudi Arabia countered that if these barriers were made explicit in this section, it “would require similar balancing language on the feasibility of solar and renewables elsewhere in the report”.

Similar discussions were had virtually CCS, with the authors ultimately like-minded to add a sub-paragraph in a footnote that details both the limits and benefits of CCS, at the urging of Germany and Saudi Arabia, respectively.

The report discusses several technologies wideness a range of maturity, removal and storage potential and costs. It finds that “all assessed modelled pathways that limit warming to 2C (>67%) or lower by 2100” rely, at least in part, on mitigation from agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU). Such approaches are currently “the only widely practised CDR methods”, the report notes.

However, it details trade-offs and barriers to large-scale implementation of AFOLU-based mitigation, including climate transpiration impacts, competing demands for land use, endangering supplies security and violation of Indigenous rights.

The report moreover discusses sector-specific deportment that can be taken in order to limit emissions and climate impacts. These transformations, it says, are “required for upper levels of human health and well-being, economic and social resilience, ecosystem health and planetary health”.

The orchestration unelevated shows near-term feasibility of version (left) and mitigation (right) options, divided wideness six sectors (top left to marrow right): energy supply; land, water and food; settlements and infrastructure; health; society, livelihood and economy; and industry and waste.

For version options, the icon shows the potential for synergies with mitigation strategies and the feasibility of these options up to 1.5C of warming, from low (light purple) to upper (dark blue). The dots in each box represent the conviction level, from low (one dot) to upper (three dots).

On the right, mitigation options are presented with their potential contribution to emissions reductions by 2030, in GtCO2e per year. The colours indicate the forfeit of each option, from low (yellow) to upper (red), with undecorous indicating options that are cheaper than fossil fuels. Some of the mitigation options with the highest potential for cost-saving are solar and wind power, efficient vehicles, lighting and other equipment, and public transit and cycling.

Feasibility of climate version options and their synergies with mitigation deportment (left) and potential contributions of mitigation options to emissions reductions by the end of the decade (right). Source: IPCC (2023) Icon 4.4a

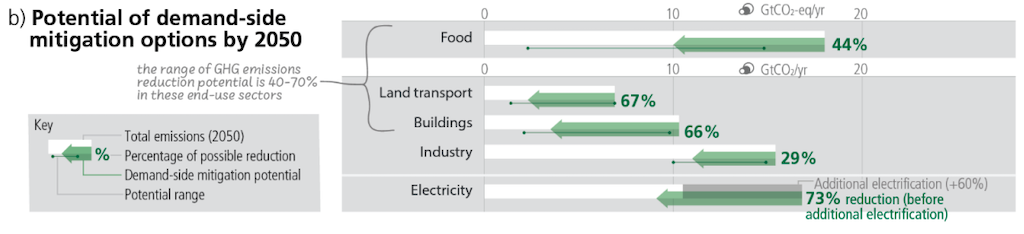

Some of these mitigation options relate to changes in energy demand, rather than supply. This includes “changes in infrastructure use, end-use technology adoption and socio-cultural and behavioural change”, the report says, noting that such changes can reduce emissions in end-use sectors by 40-70% by mid-century.

The orchestration unelevated shows the mid-century mitigation potential of demand-side changes wideness a range of sectors: supplies (including nutrition and waste), land transport, buildings, industry and electricity. The untried arrows represent the mitigation potential in GtCO2 per year.

The mitigation potential, in GtCO2e per year, of five demand-side sectors (top to bottom): food, land transport, buildings, industry and electricity. The grey bar shows the spare emissions that unfurled electrification will add. Source: IPCC (2023) Icon 4.4b

Section 4.5 of the report goes into detail well-nigh near-term mitigation and adaptation, in subsections tent energy systems; industry; cities, settlements and infrastructure; land, ocean, supplies and water; health and nutrition; and society, livelihoods and economies. At the urging of India (supported by Saudi Arabia and China) in the clearance session, the report notes that the availability and feasibility of these options differs “across systems and regions”.

On energy systems, the report says with high conviction that “major energy system transitions” are required and with very upper confidence that version “can help reduce climate-related risks to the energy system”, including lattermost events that can forfeiture or otherwise stupefy energy infrastructure.

It notes that many of the options for large-scale emissions reductions are “technically viable and supported by the public”. It adds:

“Maintaining emission-intensive systems may, in some regions and sectors, be increasingly expensive than transitioning to low emission systems.”

However, version measures for unrepealable types of power generation, such as hydropower, have “decreasing effectiveness at higher levels of warming” vastitude 1.5C or 2C, the report notes. Reducing vulnerabilities in the energy sector requires diversification and changes on the demand side, including improving energy efficiency.

The strategies to reduce industrial emissions “differ by type of industry”, the report says. Light manufacturing can be “largely decarbonised” through misogynist technologies and electrification, while decarbonising others will require the use of stat capture and storage and the minutiae of new technologies. The report adds that lattermost events will rationalization “supply and operational disruptions” wideness many industries.

“Effective mitigation” strategies can be implemented at every step of towers design, construction and use, the report says. It notes that demand-side measures can help reduce transportation-related emissions, as can re-allocating street space for pedestrians and cyclists and enabling telework.

With high confidence, it says:

“Key infrastructure systems including sanitation, water, health, transport, communications and energy will be increasingly vulnerable if diamond standards do not worth for waffly climate conditions.”

The report moreover says that “green” and “blue” infrastructure have myriad benefits: climate transpiration mitigation, reducing lattermost weather risk and improving human health and livelihoods.

AFOLU, as well as the ocean, offer “substantial mitigation and version potential…that could be upscaled in the near term wideness most regions”, the report finds. It notes that conservation and restoration of ecosystems provide “the largest share” of this potential. It reads:

Source: IPCC (2023) Full report, p73

Such deportment must be taken with the cooperation and involvement of local communities and Indigenous peoples, the report adds.

With very upper confidence, the report states that “mainstream[ing]” health considerations into policies will goody human health. There is moreover high confidence in the existing availability of “effective version options” in the health sector, such as improving wangle to drinking water and vaccine development. The report states with high confidence:

“A key pathway to climate resilience in the health sector is universal wangle to healthcare.”

The report calls for improving climate education, writing with high confidence:

“Climate literacy and information provided through climate services and polity approaches, including those that are informed by Indigenous knowledge and local knowledge, can slide behavioural changes and planning.”

It says that many types of version options “have wholesale applicability wideness sectors and provide greater risk reduction benefits when combined”. It moreover calls for “accelerating transferral and follow-through” from private sector actors.

11. What does the report say well-nigh adaptation?

The world is not adapting fast unbearable to climate transpiration – and limits to version have once been reached in some regions and ecosystems, the report says.

It says with very upper conviction that there has been progress with version planning and roll-out in all sectors and regions – and that velocious version will bring benefits for human wellbeing.

Adaptation to water-related risks make up increasingly than 60% of all documented version practices, the report says with high confidence.

Examples of constructive version have occurred in supplies production, such as through planting trees on cropland, diversification in threshing and water management and storages, the report says with high confidence.

“Ecosystem-based approaches”, such as urban greening and restoring wetlands and forests, have been constructive in “reducing inflowing risks and urban heat”, it adds with high confidence.

In addition, combinations of “non-structural measures”, such as early warning systems, and structural measures such as levees have reduced deaths from flooding, the report says with medium confidence.

But, despite progress, most version is “fragmented, incremental, sector-specific and unequally-distributed wideness regions”, the report says, adding:

“Adaptation gaps exist wideness sectors and regions, and will protract to grow under current levels of implementation, with the largest version gaps among lower income groups.”

Key barriers to version include a lack of financial resources, political transferral and a “low sense of urgency”, the report says.

The total value spent on version has increased since 2014. However, there is currently a widening gap between the financing of version and the value of money set whispered for adaptation, equal to the report.

It says with very upper confidence that the “overwhelming majority” of climate finance goes towards mitigation rather than adaptation. (See: Why is finance an ‘enabler’ and ‘barrier’ for climate action?)

It adds with medium conviction that financial losses caused by climate transpiration can reduce funds misogynist for version – hence, leaving countries increasingly vulnerable to future impacts. This is particularly true for developing and least-developed countries.

The report says with medium confidence that some people are once experiencing “soft limits” to adaptation. “Soft limits” are those where there is currently no way to transmute to the change, but there may be a way in the future. This includes small-scale farmers and households living in low-lying coastal areas.

Some areas have reached “hard limits” to adaptation, where no remoter version to climate transpiration is possible, the report says with high confidence. This includes some rainforests, tropical coral reefs, coastal wetlands, and polar and mountain ecosystems.

In the future, “adaptation options that are feasible and constructive today will wilt constrained and less constructive with increasing global warming”, the report says. It adds:

“With increasing global warming, losses and damages will increase and spare human and natural systems will reach version limits.”

For example, the effectiveness of reducing climate risks by switching yield varieties or planting patterns – commonplace on farms today – is projected to subtract whilom 1.5C of warming, the report says with high confidence. The effectiveness of on-farm irrigation is projected to ripen whilom 3C, it adds.

Above 1.5C of warming, small island populations and regions dependent on glaciers for freshwater could squatter nonflexible version limits, the report says with medium confidence.

At this level of warming, ecosystems such as coral reefs, rainforests and polar and mountain ecosystems will have surpassed nonflexible version limits – meaning some ecosystem-based approaches will wilt ineffective, the report says with high confidence.

By 2C, soft limits are projected for multiple staple crops, particularly in tropical regions, it says with high confidence. By 3C, nonflexible limits are projected for water management in parts of Europe, it says with medium confidence.

Even surpassing limits to version are reached, version cannot prevent all loss and forfeiture from climate change, the report says with high confidence. (See: What does the report say on loss and damage?)

(According to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin, China requested removing a reference to “adaptation limits” from one of the headline statements of the SPM. It was opposed by countries including the UK, Denmark, Germany, Saint Kitts and Nevis, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Mexico and Belize.)

The report says with high confidence that sea level rise poses a “distinct and severe version challenge”. This is considering it requires dealing with both slow onset changes and increases in lattermost sea level events such as storm surges and flooding.

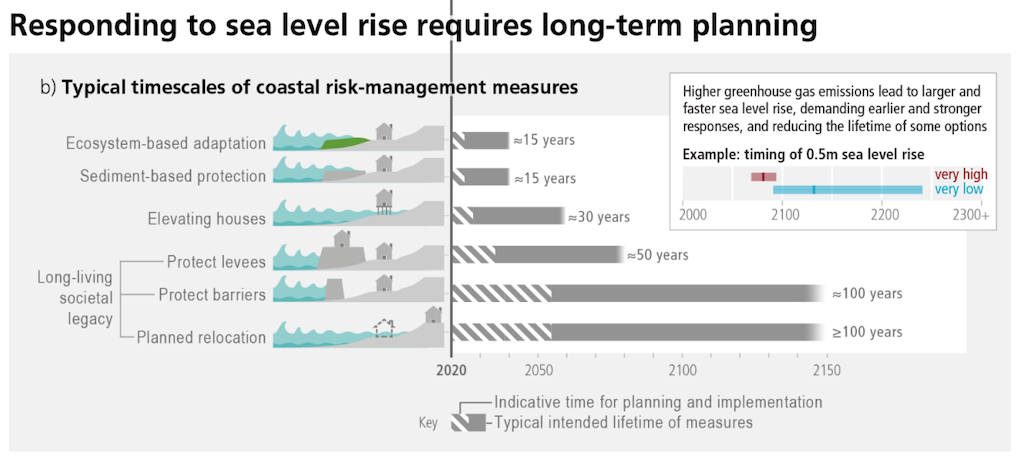

The graphic unelevated illustrates some of the version responses to sea level rise, including the time it takes for implementation and their typical intended lifetimes.

Adaptation responses for sea level rise. Source: IPCC (2023) Icon 3.4b

“Ecosystem-based” approaches include enhancing coastal wetlands. Such approaches come with co-benefits for biodiversity and reducing emissions, but start to wilt ineffective whilom 1.5C of warming, the report says with medium confidence.

“Sediment-based” approaches include seawalls. These can be ineffective “as they powerfully reduce impacts in the short-term but can moreover result in lock-ins and increase exposure to climate risks in the long-term”, the report says.

Planned relocation methods can be increasingly constructive if they are aligned with sociocultural values and involve local communities, the report says.

The report warns with high confidence that there is now increasingly vestige of “maladaptation” – deportment intended to transmute to climate transpiration that create increasingly risk and vulnerability.